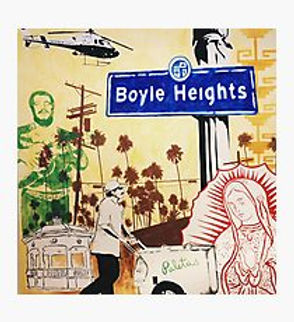

Gentrification in Boyle Heights

- Paola Lozada

- Dec 19, 2017

- 8 min read

In this blog, I talk about the origins of gentrification, the positives and the negatives of the gentrification process, and I propose a policy that can protect renters against gentrification. I point my focus on one specific neighborhood, Boyle Heights, and I establish the point of view of several residents of the neighborhood.

There are many reason as to why gentrification is an appropriate way of renewing a community, but citizens living in the communities that are being gentrified view this process as a horrible way of tearing down their culture and beliefs. While some protest the negative consequences of higher rent, others applaud the increased tax revenue. A policy ought to be implemented that both allows for progress but also protects current residents. For years, Boyle Heights has been a neighborhood confined in the rudimentary stage of gentrification, or most commonly known by its citizens as “gentefication”. But Boyle Heights has not seen as much gentrification as Silver Lake, Highland Park, or its neighbor, Lincoln Heights. With 14,229 people per square mile and 94% Latinx, Boyle Heights is facing an abundance of changes, such as new buildings and raise on rent prices. It is hard to imagine a neighborhood that has been predominantly Latinx change, as many of its citizens are opposing the now under construction areas that might tear down its prideful Latinx colors. For years, there has been talk about transforming the 14-story Art Deco Sears, Roebuck & Co. building on Olympic Boulevard into a complex of condos, retail space and restaurants. According to CoreLogic, a real estate data and analytics company based in Irvine, in the first 11 months of last year, the median sale price for homes in the 90033 zip code, which accounts for most of Boyle Heights, was $290,000, up 11.5% compared with the same period a year earlier (Delgadillo, 2016).

Oxford Dictionary defined gentrification as the process of renovating and improving a house or district so that it conforms to middle-class taste. According to Jennifer Logan and Marc Vachon(2008)[1], in the context of renters, “gentrification is part of the larger process of neighborhood renewal, and can be described as a process whereby a low rent neighborhood changes to a high rent neighborhood through redevelopment.” Historians argue that gentrification first took place in ancient Rome and in Roman Britain, where small shops were replaced by huge villas by the 3rd century, AD (Smith and Williams, 1986). One of the most notable changes that the process of gentrification brings is to the neighborhood infrastructure. Usually, the areas that have the risk to be gentrified are old and unapproachable by middle-class citizens, though they have great history which attracts potential gentrifiers (Smith, 1987).

With great change comes resistance, and Boyle Heights residents are “defending Boyle Heights against gentrification”[2]. In May of last year, a nonprofit art gallery called PSSST was preparing to open in Boyle Heights. Instead, on what should have been opening day, the gallery faced a crowd of protesters assembled in front of the space, banging drums, holding posters, and chanting slogans in English and Spanish. At some point during the day’s protest, according to the owners, someone threw feces at the window; eventually, a neighbor called the police. Groups such as Boyle Heights Alliance Against Art washing and Displacement (BHAAAD), Defend Boyle Heights and Serve the People L.A., have organized marches, held protests, and worked to make life uncomfortable for both new businesses and the people who sponsor and support them. The protesters’ tactics have been militant, insistent, and remarkably confrontational, often targeting people out for public vilification and physically chasing out unwelcome visitors.

As I sat down with Angel Luna, the leader of Defend Boyle Heights, he stated, “we’ve said ‘we don’t approve of your actions’ to the big corporations coming to our neighborhood.” He added, “They tend to ignore us, which forces us to act [violently] towards them.” He continues, “I’m sure that if lawmakers take into consideration the thousands of people affected by gentrification, our [violent] actions will be minimized.” Luna argues that most of the time, Boyle Heights residents feel unprotected by lawmakers for not making policies that protect them. “It is the duty of lawmakers to protect us, since they don’t, we are the ones that take action,” he continues, “it angers me that we are constantly seen as the bad guys when all we want is to keep our culture and homes.”

Some groups have found very extreme ways to show that they’re against changes in the neighborhood, but not all residents are on board with this militant approach. “The neighborhood shouldn’t say, ‘Get out—this place is mine.’ You want to find a balance. We want investment from the city here,” Steven Almazan, a teacher in the Boyle Heights area, told CityLab last year. Although some residents do not agree with their tactics, these groups do not desire to change their ways, as they have proven to work for them.

After assessing damage caused by a vandal who threw a rock at the window of their coffee shop, John Schwarz and Jackson Defa, owners of Weird Wave Coffee, state that they will not be intimidated by these actions. “It’s not the first time its happened,” said Schwarz, “but we will remain strong.” Back in July, the same incident happened where a vandal threw a rock at the glass door, to which Schwarz stated, “it could have been just some punk kids.”[3] Although they face constant harassment by protesters, Weird Wave Coffee is in fact a popular coffee shop. “We are very blessed to receive more love and appreciation than hate,” said Defa. “We are a small business; our intention is to better the community.” He continues, “All we can say is ‘we won’t leave’”.

Other businesses surrounding the coffee shop have nothing but good things to say about it. Guillermo Banegas, the owner of a barbershop four buildings down from the coffee shop, told a reporter from L.A. Times, “I want the coffee shop here.” He continued, “if it’s going to bring more people, the better for us.” Banegas argued that Schwarz and Defa have as much right as anyone to open a shop in the community, and he does not agree with the protesters because their reasons are very close minded. Weird Wave Coffee is only one of the many establishments that face constant harassment from protesters who refuse gentrification. Are the protesters wrong to fight against these establishments?

In 1978, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development cited data that indicated approximately 1.4 million people were forced to move from their homes annually.[4] Gentrification largely results from the effects of private markets, though it’s often “aided and abetted by actions of governmental entities.”[5] Often, the city administrators and planners perceive gentrification as an extraordinarily positive action because it signifies more revenue through increment of taxes, but these revenues come at a cost.

Several Boyle Heights residents were forced to move out of their homes due to the significant increase of rent and/or the selling of the property. “I’ve been living in my house for almost 20 years, it hurts me to move, it hurts me to leave behind all the memories that my family and I have made here,” said Rosa Ocampo, a former Boyle Heights resident. Stories like Ocampo’s fill the renovated homes of the community, as her story has become a common one. “It’s not fair for those who’ve lived their entire life’s in these homes,” she continues, “there should be a law that protects us renters from removal due to gentrification.” Ocampo is not wrong, there should be policies protecting the millions of renters that are targeted.

As a renter and resident of the community, I see both the positives and the negatives of the gentrification process. I believe that as time progresses, cities evolve and change, there is absolutely nothing wrong with that, and it would be unjust for me to not accept these changes. As I stated before, gentrification means more revenue. More revenue means more after school programs, financial benefits for residents, and a better perception of the city. When big corporations decide to invest in cities and/or neighborhoods, the image of the city changes, meaning it attracts other corporations and eventually it becomes a thriving city.

A thriving city is not always a good thing, as many citizens are pushed out. Renters are not promised protection, their rent increases, their payment does not, which means that they must find a new place to live in. When they move, their now lost homes go under renovation and are rented at a much higher price, for a much higher class. Why is this allowed, and why can’t the city officials do something about it? The truth is simple-- there is no current law or policy preventing landlords from increasing rent, and as I mentioned before, it becomes harder for renters to afford.

I propose a policy that will bring protection to current renters, regardless of citizenship status. The purpose of this policy is to provide security to renters, and to lower the percentage of violent protesters. Under this policy, landlords will be prohibited to raise rent on tenants unless they have a special reason. The special reasons consist of:

Proof that the tenant’s salary increased at least 3 percent more than when they signed the renters contract.

Proof that the number of tenants increased (based on number of residents established when contract was first signed).

Proof that tenants are being destructive to property, forcing landlord to spend more money on fixing the property (evidence can consist of photos and videos but the date when it was taken must be visible; there must be at least four occasions in less than five months for this reason to be accepted).

If property was sold, new landlord has the right to increase rent with a maximum of 150 dollars.

Proof that tenants fail to pay rent (for this reason to be accepted, landlord must prove that tenant failed to pay rent for two consecutive months).

The name of the policy will be Renters First, and it guarantees renters the protection that they deserve. I am sure that this policy will also limit, and possibly eliminate, protesters of gentrification. The main reason why these people protest gentrification is because they believe that their government is doing them wrong, most of the protesters are renters. If the policy is passed, there will be no reason to protest since they will have the rights that they believe they deserve. With this said, I urge lawmakers to pass this policy and provide the protection citizens need.

References

“CoreLogic US Home Price Report Shows Prices Up 6.6 Percent in May 2017.” CoreLogic US Home Price Report Shows Prices Up 6.6 Percent in May 2017, 5 July 2017, www.corelogic.com/about-us/news/corelogic-us-home-price-report-shows-prices-up-6.6-percent-in-may-2017.aspx. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Logan, Jennifer and Marc Vachon. "Gentrification and Rental Management Agencies: West Broadway Neighborhood in Winnipeg." Canadian Journal of Urban Research, vol. 17, no. 2, Winter2008, pp. 84-104. EBSCOhost, mimas.calstatela.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.mimas.calstatela.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=45468606&site=ehost-live.

Luna, Angel. Defend Boyle Heights Coalition. Interviewed on Oct. 24, 2017

Natalie Delgadillo @ndelgadillo07 Feed Natalie Delgadillo is a former editorial fellow at CityLab. “Defining 'Gentefication' in Latino Neighborhoods.” CityLab, 28 Sept. 2016, www.citylab.com/equity/2016/08/defining-gentefication-in-latino-neighborhoods/495923/. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Ocampo, Rosa. Former Boyle Heights Resident. Interviewed on Oct. 27, 2017.

Parkins, Helen and Christopher John Smith. Trade, traders, and the ancient city, ed. Routledge, 1998, p. 197.

Schwarz, John and Jackson Defa. Weird Wave Coffee owners. Interviewed on Nov. 1, 2017.

Smith, Neil and Peter Williams. “Gentrification of the City.” Boston: Allen and Unwin, 1986, print.

Smith, Neil. “Gentrification and the Rent Gap.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 77, no. 3, 1987, pp. 462–465. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2563279.

“SPECIAL ISSUE: Gentrification divides Boyle Heights.” Boyle Heights Beat, www.boyleheightsbeat.com/gentrification/. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

[1] Authors of ‘Gentrification and Renters Management Agencies: West Broadway Neighborhood in Winnipeg

[2] Defend Boyle Heights Slogan against gentrification.

[3] Schwarz, John told Ruben Vives, a L.A. Times reporter.

[4] LeGates & Hartman, Displacement, 15 CREARINGHOUSE REV. 207, 215 (July 1981)

[5] Bryant, Donald C. Jr. and Henry W. McGee Jr. “Gentrification and the Law: Combatting Urban Displacement.” Urban Law Annual; Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law, vol. 25, pp. 47 (January 1983

Comments